The exhibition "Witnesses" presents a dozen important personalities who are either still active at the Second Faculty of Medicine, or are active elsewhere, but graduated from the former Faculty of Pediatrics. The mottos and selected stories refer to a web project (in Czech) where the life stories of the witnesses are presented in a comprehensive version.

Click to jump

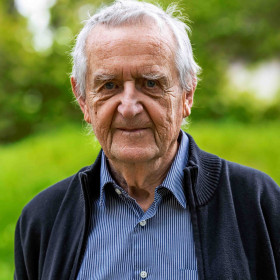

Vladimír Komárek

A paediatrician must possess empathy. Each child is unique, therefore, you need to sit down with them, kneel down, make eye contact — this belongs to the art of paediatricians and it saves a lot of time.

I remember in my first year, observing chromosomes in a microscope, photographing them and then cutting them out of photos and gluing them onto paper in the basement of the Biological Institute in Albertov. It may seem funny in the eyes of modern genetics, but back then it was a small miracle. This was at a time when Soviet "scientists" had banned genetics and its founder, Professor Bohumil Sekla, was not allowed to teach officially. Instead, he spent time with enthusiastic students underground...

Vilma Marešová

It's good to start in the countryside, you learn more and faster there. There's not so much mutual malice there, because when you rotate three or four, you need to get along with the others. Selfishness should have no place in medicine.

At that time there was a high number of diarrhoea cases; some strains of Escherichia coli were particularly severe. We used to say that at least twelve children were always on drips. The treatment was so intense that hydration with water was insufficient; administration via a drip was necessary, lasting up to ten days. The equipment was incomparable: Nowadays, special infusion needles almost penetrate veins independently, but during that period, conventional syringe needles were used. Infusions were primarily injected into veins on the head and we constructed a pillow pyramid to maintain the children's posture for as long as feasible.

Vladimír Hort

Every clinical practitioner should equip themselves with psychotherapeutic knowledge.

At the end of the 1960s, there was a revival of psychotherapy. A significant influence on this was the German Psychotherapy Society's generous offer, which allowed us to participate in the Psychotherapy Weeks in Lindau on Lake Constance free of charge, for the first time in 1967. Analysts, psychoanalysts, Jungians, and other professionals gathered, and all the leading figures in psychotherapeutic training from our country participated. In the spring of 1968, Ferdinand Knobloch organized the inaugural Czech training community in Lobč Chateau. Approximately thirty of us selected interested individuals met there. We were called the Society for the Integration of Psychotherapy and the Advancement of Psychoanalysis.

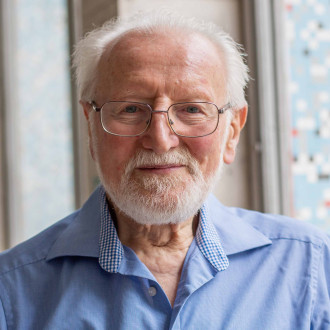

Milan Macek sr.

If one's life proves useful, they become more significant. By serving others, one may provide biological and genetic support to eternity — since life is everlasting, and even as we perish as individuals, we become anonymously immortal.

In collaboration with the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Clinic and Professor Fuchs, who collected amniotic fluid via amniocentesis, we successfully conducted the initial prenatal diagnosis in our country and the European continent in 1971. The diagnosis was conducted on a family with an elevated risk of Down's syndrome, and who already had one child affected by the condition. The mother opted for a pregnancy only with the opportunity for prenatal diagnosis. Fortunately, we demonstrated the development of an unaffected baby girl, subsequently leading to the adoption of our procedures in other centres.

Rastislav Druga

Nobody is completely perfect or imperfect. And if someone starts telling us how wonderful something will be, it won't be.

In the fourth grade, someone showed us a microscope. We were given specimens like butterfly wings, and I liked that. So I thought I'd probably have fun with a microscope. But other than that, I didn't know. It wasn't until before A-levels that it was clear that counting was out of the question, so no technology. Philosophy, languages – you thought you had to learn that on the side. History, well, that's a hobby. So there was not much left," explains Prof. Rastislav Druga, why he decided to study medicine.

Ludvíka Faladová

Patients need help and that help must be delivered honestly.

When Dr. Ludvika Faladova came to the Department of Child Neurology, she was 43 years old. "They threw me in at the deep end, after two months I went on duty. That was a terrible nerve. But I made it through. My whole life changed. Time-wise, the clinic is much more demanding than working in a lab," recalls "Adele" Faladova her early days at the hospital.

She had to pass her first and second attestations. "And to learn at the age of 45, when you've left it by then, was very difficult at first. But I did both attestations. And I worked in the clinic, I worked shifts," she says tersely, describing her transition from a scientist to a clinician.

Stanislav Tůma

You, medics, are making new history of medicine.

I was probably in my second year: We were sitting in the lecture hall at the Albertov, listening to a lecture in biology by Professor Sekla, the founder of Czech medical genetics and a professor of the, let’s say, Mendelian type. Professor Houstek, accompanied by the Vice-Dean doc. Svaty, a child neurologist, came to the lecture. There were about 250 of us from the year in the lecture hall, we were divided into two parallel groups at that time. Prof. Houstek told us about the bad situation in child care and that it was necessary to divide the faculty into three. The only medical faculty, which was several hundred years old and which has been part of Charles University since the first days – since 1348 – will be split and the individual faculties will focus on children, hygiene and general medicine with dentistry one year shorter from the practical demonstrations.

Eva Hergetová

I still enjoy it. But unfortunately, I'm mostly examining, which I don’t enjoy. So I have to, sort of, compromise.

Eva Hergetová was, in her own words, completely uninvolved in the regime at that time. Back then, there was a vetting process every year and she was facing dismissal from the Institute of Anatomy. "And the argument of one Chairman of the committee was: she is not a doctor, she cannot motivate students clinically. That's when Cihak told me to study medicine."

On the verge of turning thirty – while working and teaching at the Institute of Anatomy – she became a student again.

She had to do propaedeutic in a group with other medical students. "I don't remember the number anymore, but I think we were number two. There I found myself among students ten to twelve years younger. Some of them immediately started being on first name terms with me. Others were more formal – especially those who were in our preparation course. They worked as cleaners for us and suddenly I was their classmate. Anyway, in the exam, we were kicking each other under the table and helping to each other. I went to parties with them. I fit right in."

Pavel Mareš

Negative results are generally very difficult to publish, which is a shame since it could prevent other people from wasting their time. This is something I have never appreciated.

However, the pharmaceutical industry commonly provides more significant remuneration. Is this not appealing to you? Or perhaps you prefer working in the lab and conducting your own research?

I enjoy it. And as Dr. Bures stated previously, individuals who remain in experimental work tend to find the work itself more fulfilling than a higher salary. And he's right about that, because the motivation is strong.

How long do you plan to continue your research activities?

I hope to be in the lab for a while. I would have the genetic basis for it. In my mother's family, to which I belong, it was quite common for individuals to reach the age of ninety with full physical and mental capability, even at a time when there were only a few centenarians in our country. As a child I planned to live to be 100, which was very presumptuous at the time. Nowadays, it's not such an outlandish goal, with many people living to100. So I hope to live for at least another fourteen years until I reach one hundred.

Milan Cholt

All this modern technology only makes sense if it helps someone.

How do I see the future of medicine? It has to be one that keeps helping people. You can't become a scientist just to say, "Yeah, he's sick! He's very sick..." and not care about the patient anymore. Medicine must always be about helping people. That's the way it's always been, and I don't think there's any other way. Those “fogeys” that can’t be bothered to help, they don't belong in medicine... And there's no point in talking about new technology or artificial intelligence. Who knows what the world will look like in 50 years and what will turn out to be a dead-end street.