Prof. MUDr. Josef Skála, M.D., Ph.D., FRCPC

Dear readers. Let me apologize at the beginning of today's interview for its unusual length. You will notice that the conversation is a bit longer than is customary on our website. When you begin reading, however, you will see that the story and thoughts of Prof. Skála are not only fascinating, but expressed in an almost poetic language; I found it impossible to edit. Let your soul be touched by his words...

Who is Prof. Skála?

Receiving the F.N.G. Starr Award

I have approached Prof. Jan Starý – Head of the Department of Oncology and Hematology and of the Pediatric Oncology Institute to introduce professor Skála. His words emphasize the importance of Prof. Skála's contribution to Czech medical science, pediatrics and Czech culture in general:

‘Professor Skála is a Visiting Professor at Charles University. I met him in the early 1990's when he offered his help with the development of the bone marrow transplantation program in our hospital. We have collaborated on several large research projects funded by the Czech Ministry of Health and by the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. These were successfully completed in late 1990's, and the results were published and presented by us at several conferences, and also during my visit to the University of British Columbia and the B.C. Children's Hospital.

While visiting Vancouver, I had the opportunity to see the great respect for Dr. Skála's work. His name appears in the University President's Office among the alumni of highest achievements. He is an internationally recognized medical scientist and a brilliant teacher of graduate students. In addition, he founded a Czech theatre in Vancouver, directed and acted in many Czech plays and, after 1990, produced guest performances of many Czech artists. The Theatre Around the Corner provided an anchor for the preservation of the cultural roots of the Czech and Slovak ethnic community in British Columbia. His work in theatre also advanced our culture among the Canadian community at large – his dramatic reading of the ‘Good Soldier Schweik’ on Canadian radio was unforgettable.

He is a boater, traveler, excellent photographer, storyteller and a very popular member of his community. He regularly contributes to the Czech internet daily, the ‘Invisible Dog’. In addition, he has a very outgoing and friendly personality. I was not surprised, that such a ‘renaissance’ man has been awarded the highest recognition a Canadian physician can receive from his peers.’

Our cyber-space interview began with a bit of reminiscence... ‘The six years (1958–64) I spent at the Faculty of Pediatrics of the Charles University of Prague, the predecessor of the 2nd Faculty of Medicine, are deeply imbedded in my heart, and have probably significantly influenced my entire life. I realize that my reminiscences may appear not only archaic, but perhaps irrelevant to students to-day, but please believe me that the history of the faculty you are fortunate enough to attend, and lives of professors who had created that history, are the principal building blocks of the pride, with which you should cherish your ‘Alma Mater’ for the rest of your lives...’

The weaknesses – a cigar and a glass of red wine

When and where were you born, when and where did you graduate and what direction did your life take afterwards?

Well, that's not a narrow question and thus you have to excuse a somewhat lengthy answer. It's been almost 70 years since I was born in a merchant family of the Little Quarter (Malá Strana) in Prague. The Josef Skála ‘colonial’ store and later the coffee wholesale business was established by my grandfather at the turn of the last century on the corner of Mostecká and Lázeňská streets. In those times the Little Quarter was nothing like it is now. It was an enclave of village-like old town community, where everybody knew everybody for generations, and where my childhood felt almost like the Neruda's nostalgic ‘Malá Strana Stories’. During the war I have also lived for a considerable length of time on a small secluded farm in southern Bohemia. The romantic isolation of that place is apparent even from its postal address: Klokočná near Vranovská Lhota, near Vranov, last postal outlet Přestavlky near Čerčany. My only friend there was Péťa – a St. Bernard dog. Purportedly my principal residence was in his doghouse, because my grandma, suffering from arthritis, soon gave up the struggle of pulling me out. She simply covered Péťa's dog-house with a blanket, and since I refused to eat anything which he did not, she started to supply Péťas dish with food intended for me. One may say, that I spent a significant part of my formative early development in a dog-house, an experience which became extremely useful in my later life.

After the communist takeover in 1948 my family was, of course, brutally persecuted, and the slogan of the proletariat promising ‘bright tomorrows’ translated into years of imprisonment and forced labor for my father and many of my relatives. In those dark ages of the totalitarian regime, the only bright light was my studies at the famous Jan Neruda high school, where I have discovered the love of my life – the arts, and specifically, theatre. As could be expected, the political profile of my family, i.e. the ‘despised bourgeoisie destined for elimination’, carried with it no hope of post-secondary education for me. But, a miracle happened. The combination of a decent old principal, my top grades, and the fact that my family had known Prof. Brdlík (founder of Pediatrics in Czechoslovakia, whose limping Dachshunds and many colorful birds in his surgery were greatly admired by me – one of his little patients – and may have actually even influenced my later decision to specialize in pediatrics) and Prof Houštěk (who was then the Dean of the Faculty of Pediatrics), had opened the back door of the so called ‘Dean's exemption’, and in 1958 I became a medical student. It is interesting to note, that the ‘miracle’ of my admission wasn't probably that miraculous after all – most of my schoolmates were indeed kids from the despised bourgeoisie or intellectual classes. Many of them also escaped the ‘communist paradise’ in 1968, and in later years there was almost no large Faculty of Medicine in North America, where I would not meet at least one of my friends, occupying a full professor's chair.

My love for theatre continued. With a group of enthusiasts, I established the University Theatre of Classical Comedy, and over the next years directed and acted in a number of very successful productions in Žižkov Theatre (today's home of the Cimmermanns). Subsequently I have also been involved in the beginnings of the ‘poetic’ Theatre Viola with Dr. Martínek and Jiří Ostermann.

Let's return to medicine. As you can appreciate, being from the ‘enemy class’, our family was very poor. The only means by which I could contribute to the meager family income were my summer jobs in the ironworks of Poldovka in Kladno, and my performance stipend from the university. Consequently, in order to get badly needed cash, I had to study quite hard. The money was not, however, the only reason. Prof. Rašková and Prof. Poupa inspired me to get involved in the student research program. It is interesting to divert a bit here and to note, that in contrast to the Faculty of General Medicine, the Faculty of Pediatrics had among its professors a number of brilliant medical scientists and clinicians, whose loyalty to the communist ideology was doubtful if not completely absent. It may have been because the Faculty of Pediatrics kept a low profile as a relatively young and small school (50–60 students in a class), but it played a huge role in our education. Being exposed to pedagogues of immense intellectual power and experience, and at the same time, possessing incorruptible human and moral dignity, could not but deeply influence our future lives. I shall never forget Prof. Benešová and Rašková, Prof. Hněvkovský, Jedlička, Vahala, Kafka and the extraordinary personality of Prof. Rudolf Peter. It was they, who instilled in me the pride of being a part of Charles University's age-old community, and from them I have learned the true calling of a university pedagogue. The scope of their talents encompassed not only their discipline, but reached also into the realm of humanities and arts. My perhaps most influential role model became Prof. Otakar Poupa, who was later also my research supervisor and with whom I stayed in close touch even during our time in exile. The Faculty of Pediatrics collaborated also with the Institute of Physiology of the Academy of Sciences, where I worked under the supervision of Dr. Petr Hahn, with whom I later also collaborated for many years in Vancouver. My work was presented at a number of national student research competitions, and I believe that a couple of times I even won.

Let me say here, that I am truly grateful to Destiny (or whoever up there determines our earthly travels) for my six years at medical school. I came to the conclusion later in life, that regardless of whether one subsequently makes a living in clinical medicine or not, the education we obtained was probably the best possible introduction to the wonders of life in general. I sincerely hope that the current students of this faculty also benefit from such an education.

I graduated with distinction in 1964. My hope of entering a postgraduate training at the Research Institute of Child Development (a position offered to me by Prof. Houštěk after a successful competition) was, however, immediately crushed by the hard fist of the proletariat. As a known ‘enemy of the right ideology’ I was shipped to a small regional hospital in Aš on the western border. The following 2 years of survival in the truly appalling environment of this devastated city, located on the wrong (eastern) side of the Iron Curtain, could be described in a Hrabal-like absurd novel. Let's just say that I learned a lot, and after immense difficulties I did finally start my research training. As could be expected, I keenly participated in the Prague Spring (together with about a dozen of the postgraduate trainees from many disciplines we founded the ‘Association of young scientists’ and tried to change the idiotic and politically-motivated curriculum), and as could also be expected, escaped the ‘just’ punishment for such an ‘anti-state activity’, that surely awaited me following the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the ‘friendly’ tanks of the Warsaw Pact on August 21st, 1968, by illegally crossing the Iron Curtain in the right direction.

Skála's photo of a Vancouver morning

How did you experience the exile?

It almost feels like I have been privileged to live several, separate and mutually exclusive, lives. Exile had kicked me into a completely unknown immense space. It felt like an escape from a crammed smelly cage into a vast universe with no supporting walls in view. Yes, it was very scary, but at the same time it offered an infinite number of choices. The degree of one's freedom, however, parallels the degree of responsibility one is willing to assume. To be absolutely free necessitates absolute self-reliance. One must become completely responsible for both successes and failures, and should learn to blame nobody but oneself for the latter. Freedom means the elimination of barriers, but also of excuses. Fortunately, I realized all that very soon, and quickly learned to rely on nobody but myself. It was very hard work, granted, but never without purpose, and, thankfully, it brought rewards as well. After a year at the Wenner-Gren Institute in Stockholm, where I published a series of papers, I won a competition for a postdoctoral fellowship offered by the Canadian Medical Research Council, moved to Vancouver, passed US and Canadian exams for my medical degree, completed my formal research education by defending a Ph.D. in physiology, spent a year at the Hammersmith Hospital in London, qualified as a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and eventually (1984) advanced to the position of a full professor of pediatrics, Ob&Gyn and of physiology at the University of British Columbia in the spectacular city of Vancouver. I worked for a number of years in the field of molecular endocrinology and was truly blessed by collaborating with a brilliant British biochemist Dr. Brian Knight at the edge of basic studies of protein kinases and their role in intercellular communication. From that it was only a small step into experimental research in oncology, which I entered at the time when autologous bone marrow transplantation was first developed. I had been lucky to develop a new approach to the graft purging without any use of cytotoxins, and applied it to a new therapeutic protocols in neuroblastoma and pediatric leukemias. My luck did not run out, the Iron Curtain tumbled down, and I could re-connect with my old ‘Alma Mater’ at the beginning of the 1990s. I'd like to believe that I helped a bit with the development of the bone marrow transplantation programs in Motol. I was welcomed by Prof. Koutecký, whom I had immediately recognized as one of the above mentioned rare breed of outstanding university professors, and whose weakness for an occasional Virginia cigar resonated well with my enjoyment of a good cigar or one of my many pipes. I have arranged for a sabbatical study leave to spend 1993/94 in Prague, and collaborated with a number of excellent researchers on several large clinical trials. In addition, we succeeded in establishing an official link between the Charles University and the University of British Columbia. It was signed, interestingly enough, by Prof. Radim Palouš, the then president of Charles University, whom I had known well as my teacher of chemistry at the Jan Neruda high school. Of course, not all of our plans actually materialized, but for me personally, if the only result of those years of work had been my meeting and becoming good friends with Prof. Jan Starý, I couldn't wish for a better reward. Finally, being named a Visiting Professor of my ‘Alma Mater’ was the proverbial ‘icing on the cake’; it made me very grateful, as it somehow brought the spiral of my life in medicine back to the point where it started those many, many years ago.

Celebrating the 69th b-day with sons

Peter and Martin

What has influenced your selection of the field of interest? There were actually a few of them, weren't there?

Quite frankly, many times it may have been serendipity or opportunity, but my inherited curiosity and bull-headed perseverance not to give up until a reasonable answer is found certainly played a principal role. But again – that can probably be said about any creative endeavor. Curiosity and perseverance to find answers should be, at least in my view, the principal result of education. Enriched, perhaps, by the ability to risk transgressing the borders of safety by asking questions which may seem naive, perhaps even stupid, and which may throw unfavorable light on the questioner. Many are those who, being short-sighted or lazy, do not distinguish between impertinence and feeblemindedness. No colleague or educator should be excused for that. Impertinence, or courage if you like, to pose unpleasant questions, and to stir the tranquil waters of inertia, is a god-given right of every student and scientist. Practical application of this right was the principal difference between North American students and Czech students, as I have remembered them from Prague. I truly hope that this is no longer the case.

As you may have noted, the path of so-called applied research seems to be favored by more and more medical scientists. It's safe, it brings research grants, and it results in a number of papers with a cornucopia of co-authors. As soon as the minimal required number of tables and figures is collected, another publication joins the C.V. Most such papers end with something like ‘further research will be necessary before...’. I am probably old-fashioned, but except in some very rare instances, I see no reason to publish anything before the definite answer is reached. I also sincerely believe, for example, that it is much more likely a true break-through in our understanding of malignancy will come from a biologist working on a purely curiosity-oriented project on the sea urchin, than from thousands of applied research papers.

In the part of Jupiter dressed as white Harlequin

in V+W play ‘Heavens on Earth’

You have also devoted your life to both professional and amateur theatre. What have you derived from it, and do you see any parallel between theatre and medicine?

Arts in general and theatre in particular, have always been a significant part of my life. In that the Fates were generous to me. I truly believe that the profession of physician did, does and always will extend past the borders of exact science deep into the realm of humanities, and thus arts. I see no difference between scientific and artistic creativity. Furthermore, the possibility to intermittently switch from the scientific frame of mind into the artistic enrichment of the heart provides not only a needed rest, but often also stimulation and inspiration. At least for me, it always worked that way. There are many historical and current examples of excellent physicians, who were also accomplished musicians, painters, writers. I deeply believe that a physician should never be only a craftsman, even if an excellent one. His or her task is not only to understand the human body and its functions, but to be a facilitator of human life in all its dimensions. Physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual. There were times when the North American medical schools admitted students exclusively on the basis of their grades in pre-med science courses. No attention was paid to the fact that high marks in sciences do not indicate the ability to establish a human contact with a patient. That policy, of course, resulted in the proliferation of ‘alternative’ healers. They, in contrast to the rushed doctor with a laptop on his examining table, extend a hand and ear to their clients. I had always fought such selection criteria for future physicians, and I see with satisfaction that recently many schools have begun admitting more mature students with backgrounds in humanities. We should re-discover that a patient seeks from his doctor human understanding and touch first. Only after a spark of human touch is elicited, a physician may reach into his bag of medical knowledge. A student on rounds, who first reaches for the chart while presenting a patient, instead of touching his hand and exchanging a few kind words, should be immediately ordered to leave the room. He lacks the sensitivity and emotional aspect of his profession, which only humanities and arts cultivate. Professors of medicine should perhaps be also assigning their students reading of literature, listening to classical music, visiting galleries and attending theatre performances. Most of my best remembered professors did just that.

Even though it seemed impossible at the beginning, I have managed to continue my work in theatre even in exile. During my year of postgraduate training in London, I have managed to bring my English to a level that I feel and like it as much as I love my mother tongue. After returning to Vancouver, I was admitted into the ACTRA union of theatre professionals and started to work frequently in radio drama for the national CBC network. It started with a dramatic reading of Hašek's ‘Good Soldier Schweik’, which had been broadcast in 15 episodes all over Canada and was well received by the listeners. It was followed by about 40 radio productions and even some awards for my performance. My longing for theatre in my mother tongue was satisfied in 1975, when I co-founded the Czech ‘Theatre Around the Corner’ (www.theatrearoundthecorner.ca), where I have directed, produced, done stage design and sometimes also acted in about thirty productions over the following three decades. We even produced some world premieres of plays by Czech dissident authors, I have translated a couple of them to English and staged them on Vancouver's professional stages. In a few other Czech plays I have worked as an actor. After the ‘Velvet Revolution’ our group produced guest performances by many top Czech actors and singers throughout Western Canada and the USA. Some of the artists became close friends and I enjoy following their work during my annual visits to Prague. And imagine – during my sabbatical stay in Prague in 1994 I had the pleasure of acting in a radio drama in Czech, working the mike with the legendary Rudolf Hrušínský Sr. and Mr. Václav Postránecký, who subsequently became a close friend.

Why did you decide to retire prior to reaching 60 and have recently also resigned from your work as the artistic director of the Theatre Around the Corner?

Being an evolutionist, I believe that the transition of leadership to the younger generation should occur in a timely fashion. One should step aside when still at the plateau of his or her career. Not perhaps at the summit of it, but certainly prior to the obvious decline of one's creative powers. This is not, unfortunately, a central European tradition. There, the interpretation of the term ‘former’ director, head, minister etc., is interpreted as indicating that he was either stupid or a thief. A timely departure is not, however, anything unusual in North America. Retired university professors, for example, receive appointments of Professors Emeriti, and are not only respected, but also expected to offer advice if and when needed. Their former positions can thus accommodate new ideas and directions. It's not necessary to add, that new does not necessarily mean better, but the change of guard comprises evolution and as such should be respected. I, for one, certainly do not regret my timely retirement; it gave me the opportunity to explore new interests and activities, allowed me to wander extensively with my camera, catch up with reading, listening to music and cooking for my grandkids. Time seems to run faster and faster. Let me add one final argument in favor of a timely retirement – it is said that with old age comes wisdom; unfortunately the truth is that old age often arrives alone.

At the Masaryk Award ceremony

with Eva Solar-Kinderman

Have you ever considered returning back to Prague? Do you follow our current events?

I flirted with the idea a bit at the beginning of the 1990's. After spending a whole year in Prague, however, I realized that one cannot step twice into the same river. In the depth of my heart I shall always remain a ‘Little Qarter man’, I will always cherish my pride to be a graduate of the time-honored Charles University and my thoughts and feelings will always reflect that I was first nursed by the Moldau river. Over half of life spent in a mature democracy, however, severely limits my level of tolerance for pettiness, with which the young democracy of the Czech Republic will struggle for a long time yet. I do follow the news, admittedly mostly on the ‘Invisible Dog’ website (to which I occasionally even contribute), and I certainly wish my homeland nothing but the best. I visit Prague annually with my better half – the concert pianist Eva Solar-Kinderman, and fully enjoy dividing my life between the two most beautiful cities in the world: the spectacular young Vancouver and the venerable magical Prague. Even my youngest grandson visited Prague, has a double citizenship, and has already learned a few sentences in Czech.

On the other hand, let me reiterate my belief that the several generations immersed in the lies of a criminal ideology resulted in corrupted moral fiber of the whole nation. To fix that will take a long time. Particularly so, since the ‘Velvet Revolution’ failed miserably to reconcile the society with its guilt. I see evidence of that even in the behavior of some of my relatives; unfortunately, I have failed to establish a dignified human relationship with those who grew up during the ‘normalization’ period of the 1970's and 80's. Without ever realizing it, the true values of human life will probably always remain beyond their grasp. Regretfully, I shall probably never know whether their kids will be different. Let me emphasize, however, that such a fault of character certainly does not apply to all. I admire many highly moral and principled people in the Czech Republic, and not all of them are my relatives and friends with whom I grew up. To be fair, I should also note that even among the Czech and Slovak exile community one frequently meets typical spine-less ‘Čecháčky’ (this phenomenon certainly deserves a thick book, but some excellent analyses have already appeared in brilliant books like Ivan Diviš: ‘Theory of Reliability’, Jan Zábrana: ‘The Whole Life’ and even in some movies by Jarchovský and Hřebejk).

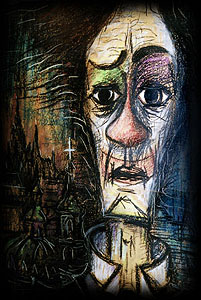

Skála's painting ‘Prague Magi’

You have signed, among others, the petition to prohibit the Communist Party, and, at least according to the internet, have spoken extensively against the communist ideology. Is it true?

Absolutely. For me it's not an option but a necessity. Six years ago I also started an initiative ‘We must not forget’, which resulted in the establishment of a database ‘Lives Derailed by Communism’ in the Centre for Documentation of Prof. Prečan. It's under the jurisdiction of the National Museum, and it contains hundreds of verbal and written submissions documenting the history of individuals and families, whose lives were destroyed by the communist regime. Twenty years since the fall of the communism in Europe gives enough distance to finally document the full extent of its crime. Historians have to acknowledge, that the crime reached far beyond the well known and documented individuals and groups, and touched upon the lives of the entire nations. Every family and individual were victims, either as the persecuted or as the active or passive collaborators. Unless the crime of communism is documented as much as the crime of fascism, and unless it is embedded deep in the memory of our civilization by scientific and artistic reflection, the danger of repeating it lurks close on the horizon.

Are you familiar with the current movement among Czech physicians ‘Thanks, we are leaving’ in which they express dissatisfaction with our health care system, our education and remuneration? What is your opinion?

I hesitate to form an opinion because I don't live there. I can only sincerely hope that it will be members of my profession, who will first reach a truly moral balance between their rights and their responsibilities within the context of the whole society.

On a trip with the favored means of transportation

You have recently been awarded the highest recognition the Canadian Medical Association can bestow on a Canadian physician, the F.N.Starr award, for your ‘significant contribution to medical sciences, practice and teaching as well as for your work in the arts, specifically the theatre’. How do you perceive it? It is not your only recognition, can you mention those you value the most?

I am afraid that life achievement awards somehow indicate that one's life is nearing its end. That he is, perhaps accomplished, but certainly really old. The other side of the coin is that being old, and thus feeble-minded, allows one to shamelessly enjoy the attention. What recognitions warm my old heart? About twenty years ago the Sunday magazine of Vancouver's daily published a long leading article about me under the title ‘Vancouver's renaissance man’. Of course I did enjoy it, but secretly derived particular pleasure from the fact, that that ‘Vancouver's’ fellow was really a ‘Little Quarter man’. When the University of British Columbia celebrated its 75th birthday in 1991, seventy-five out of all past graduates were selected as ‘Alumni of achievement’ and entered into the ‘Hall of Fame’. There were about 40 of them still alive, and among all the politicians, judges and industrialists, only two people somehow did not fit the fold. An actress and myself. Again, my strange sense of humor did not fail to note, that in contrast to my original ‘Alma Mater’, which was then 643 years old, the celebration I participated in was in fact the birthday of a toddler. Of course I have truly enjoyed receiving, on behalf of the Theatre Around the Corner, the Gratias Agit award (for advancement of Czech culture abroad) from the Ministry of External Affairs in 2008. Once again, the icing on the cage was the fact, that we received the award in Czernin Palace from the hands of Duke Schwarzenberg, whom I have greatly admired for a very long time. Last year my old heart was truly warmed by receiving the Masaryk Award from the Czech and Slovak Association of Canada. Just the name brought tears to my eyes. And the F.N.G. Starr Award? That was so unexpected that when receiving the phone call from the President my heart almost gave up and the award was almost given in memoriam. It is the oldest and highest award a physician can receive from his peers. It's referred to as a ‘Victoria Cross’ of Canadian medicine and not awarded every year. The first recipients in 1936 were Banting, Best and Colip, the Nobelists who discovered insulin, and my award was the 45th in line. Just the fact, that this recognition fell upon a refugee, who came here 40 years ago without any recognized qualification and with empty pockets, still amazes me, particularly after reading the C.V. of the previous 44 recipients. Again, an interesting fact. I was not the first recipient who graduated from Charles University. The awardee in 1987 was Prof. Hans Peter Selye, the discoverer of stress theory, who graduated from Charles University in medicine and chemistry in 1927.

The very formal ceremony was held last August during the Annual Congress in Niagara Falls. As the well-known old song says, once again ‘there stood above the Niagara Falls an old wanderer and recalled his first love’. Well, there was certainly more than one love for me to remember, but one of them was my ‘Alma Mater’. In my acceptance speech I did acknowledge not only Charles University, but also the hundreds, perhaps thousands of its graduates who, spread all across Canada, have also contributed significantly to their new homeland. For me personally, the recognition indicated that I have hopefully repaid Canada for the generosity with which she welcomed me forty years ago and gave me space to pursue my dreams.

The deepest love, of course, which I felt and expressed in my speech was for my parents, who selflessly gave everything to me, and for my beloved two sons Peter and Martin, whom I have brought up as a single father from the ages of 5 and 3. I could never wish for better sons. They are both great guys and excellent dads for my 3 terrific grandkids. It looks like they have learned from experience that fathers are supposed to be the caregivers for their kids. Unfortunately I could not share my award with my beloved cat Mourek, with whom I have shared house for 17 years, and who unfortunately preceded me last year into the next dimension of the Akashic field.

Would you like to say something to our students?

To always cherish, as much as I do, with great pride the name of Faculty of Medicine of Charles University. And to remember always, particularly so during the many hard moments in the life of a physician, the verses of Fráňa Šrámek written almost hundred years ago: ‘No, you will never cull the stars from the skies, but you must firmly believe that you will...’

Thank you for the interview

-md-